By Tim Young, Venezuela Solidarity Campaign

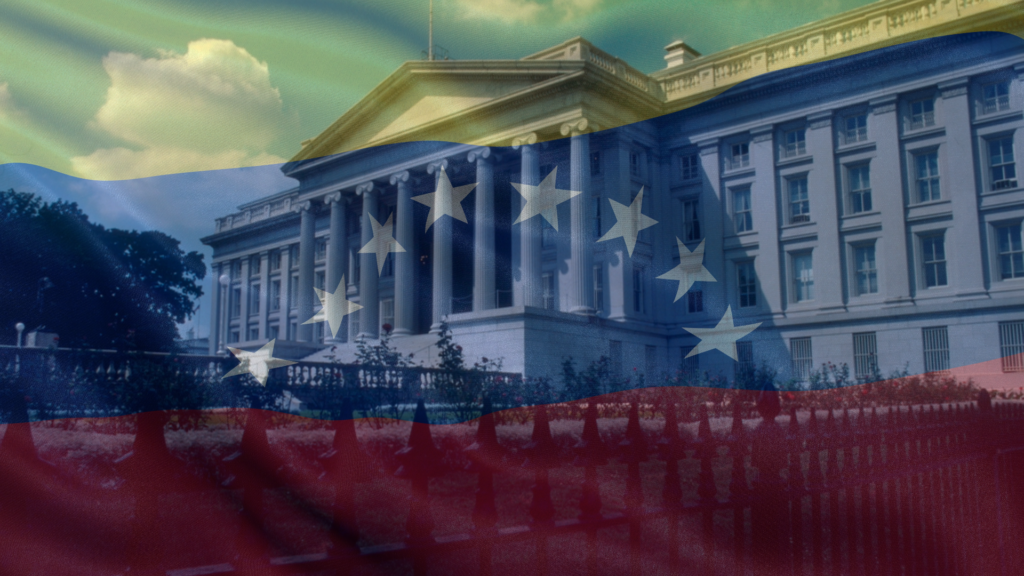

Prompted by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and its impact on oil supplies, and also by recent events in the Middle East, the US has eased some of sanctions that it has been levying on Venezuela in pursuit of its goal of ‘regime change’.

The sanctions which are part of the arsenal of illegal coercive measures the US has been employing against Venezuela since President Obama first declared the country to be an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States” in 2015. Under Trump, sanctions were ratcheted up to match the ongoing blockade of Cuba.

On 18 October 2023, the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued a number of licences suspending key sanctions on Venezuela.

The specific licences are:

- General Licence 44, which authorises state oil company PDVSA, as well as joint ventures where it holds majority stakes, to produce and export oil to US customers. The document also allows the provision of goods and services, new investment, and the settlement of debts with oil and gas shipments. It is valid for six months.

- General Licence 43 authorises dealings involving Venezuela’s state mining company Minerven as well as transactions with the Venezuelan Central Bank (BCV) and Bank of Venezuela (BDV), the country’s largest financial institution.

- A further licence has been amended to remove bans on secondary trading involving Venezuelan state and PDVSA bonds.

- The last licence allows the Venezuelan state airline Conviasa to execute transactions related to the repatriation of Venezuelan citizens from Latin American countries.

The Venezuelan government has welcomed the move while still calling for the lifting of all sanctions. President Maduro described the OFAC licences as a “first step of a necessary global agreement”.

It is unclear as yet how this will play out in practice. The new licences lift the oil embargo that blocked all exports to US customers. The Venezuelan government has already started to sign new spot contracts to export fuel oil and asphalt cement, for payment in euros.

But given that Venezuelan state entities have not regained access to US-based bank accounts, how any new shipments to the US will be paid for is unclear. While potential US buyers might not be allowed to pay directly for crude oil shipments from Venezuela, the licences open the possibility of swap agreements, such as oil-for-fuel. Another possibility is that Venezuelan creditors may negotiate crude oil-for-debt deals.

While it is unlikely that Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PDVSA, can increase production quickly, the possibility of exporting to Western customers at market prices could produce additional oil revenues of up to $3.6 billion annually – provided the US do not amend or revoke these new authorisations

Dialogue results in new accord

The US Treasury has stated that it is prepared to reimpose the sanctions at any time, should the Venezuelan government “fail to follow through on their commitments.”

The commitments referred to those agreed through the resumption of dialogue in Barbados between the Maduro government and the opposition ‘Unitary Platform’.

Called a “Partial Agreement on the Promotion of Political Rights and Electoral Guarantees for All”, the Barbados accord sets out conditions for the 2024 presidential elections. It rejects any “political violence” against Venezuela or its state institutions and lays out twelve points concerning the presidential vote.

These include holding the election in the latter half of 2024, updating the electoral registry, promoting a balanced media coverage and publicly recognising the results. Both sides have agreed to invite international observers from organisations including the African Union, the European Union and the Carter Center.

The agreement also deals with electoral guarantees for candidates, including allowing all candidates being allowed to stand provided they do not break the law or the Venezuelan Constitution.

This will undoubtedly be a contentious issue, given that that the far-right politician Maria Corina Machado, who won the opposition’s primary to be the Unitary Platform’s candidate standing against Maduro, is currently barred from holding political office for 15 years for her alleged involvement in regime change plots.

Both sides also pledged to “defend the assets and property” of Citgo, a US-based subsidiary of the state oil company PDVSA. Currently, a US court has approved an auction between January and May 2024 of shares in Citgo which is valued at between US$ 10-13 billion.

Proceeds from the auction will pay businesses claiming compensation for expropriations carried out by Chávez over a decade ago. President Trump handed control of CITGO to Guaid? and his allies in 2019, whose chronic mismanagement has opened up CITGO to these claims, amounting to over $23 billion.

It is unclear how the Venezuelan government or the opposition can defend Citgo without US government intervention.

While the accord marks a new stage in the dialogue between the Venezuelan government and the right-wing opposition, the US State Department has stated that it will only renew the newly-granted licences if the Maduro government abides by the accord’s commitments and also releases US and Venezuelan political prisoners. The US calculates there are at least 268 Venezuelan political prisoners and three ‘wrongfully detained’ US citizens in jail, although Venezuela would dispute the term ‘political prisoner’ for those convicted, often for very serious law-breaking, such as coup plotting, arms trafficking, criminal conspiracy and colluding with a foreign government.