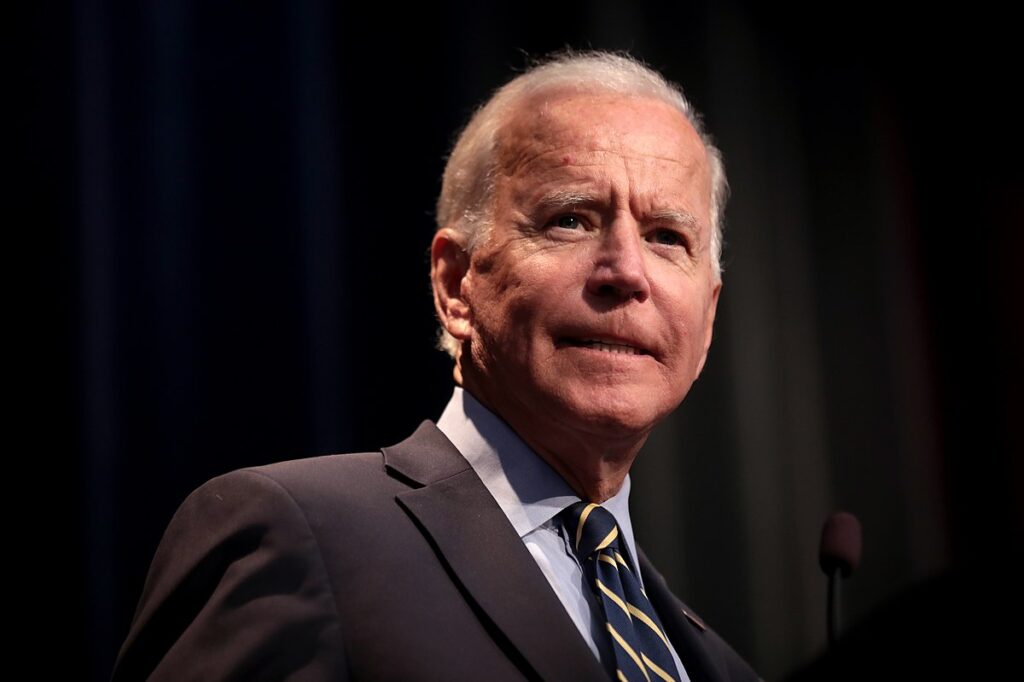

While the US president is pursuing a more progressive domestic policy agenda in many respects, his position towards Venezuela appears to be alarmingly similar to Trump’s, warns TIM YOUNG

DONALD TRUMP’S approach to Venezuela proved to be singularly unsuccessful. As president he ratcheted up sanctions against Venezuela’s elected government in an attempt to bring about “regime change.” Over Trump’s time in office, sanctions against Venezuela were widened and intensified into a blockade of its commercial and financial business dealings.

As the blockade tightened, the impact on the lives of ordinary Venezuelans, particularly the poor, the sick and the elderly, became devastating, with far-reaching effects. The Washington-based Centre for Economic and Policy Research calculated they led to more than 40,000 deaths in 2017-18 alone.

The dire impact of sanctions has attracted the UN’s attention. In January 2019, Idriss Jazairy, the UN’s special rapporteur on coercive measures’ impact on human rights, voiced his major concerns about them: “Coercion, whether military or economic, must never be used to seek a change in government in a sovereign state.”

And two years later, UN human rights rapporteur Alena Douhan concluded from meetings with various Venezuelan sectors that “the sanctions and unilateral coercive measures applied by the United States and the European Union, as a deliberate tool to achieve regime change in Venezuela, flagrantly violate international law and all universal and regional human rights instruments.”

This foreign policy failure by Trump rested on three false assumptions: that Venezuela’s armed forces would change sides, that President Maduro lacked popular support and that Venezuelan allies — especially China, Russia and Cuba — would ultimately desert the Maduro government.

Yet none of these assumptions have proved correct, leaving Biden still continuing to support the self-declared “interim president” Juan Guaido and promising to work with partners across the region “to exert pressure on the regime so the country can peacefully return to democracy.”

But there are signs that the US government does not enjoy unqualified support for this policy.

In March for example, the United Nations human rights council approved a resolution urging all states to stop adopting unilateral sanctions as “tools of political and economic pressure.”

The UN body crucially reaffirmed “the right of all peoples to self-determination” — Venezuela’s key demand of respect for its sovereignty — while urging perpetrators to put “an immediate end” to the measures which are not in accordance with international law and the UN Charter.

Although the European Union is still upholding sanctions against Venezuela, after the December 2020 National Assembly elections it now refers to Guaido as a representative of the outgoing National Assembly, effectively no longer recognising him as “interim president.”

The EU has recently gone further, with Josep Borrell, its High Representative for Foreign Affairs, saying there could be a political agreement between the Maduro government and opposition factions regarding the next regional and municipal elections in Venezuela.

There are signs, too, within the US governmental apparatus of divergence from Biden’s position.

An official US Congressional Research Service report issued in late April acknowledged: “The failure to dislodge Maduro from power demonstrated the limits of US and other international efforts to prompt political change in Venezuela. Unilateral US policies, such as oil sanctions, arguably worsened the humanitarian crisis in the country and caused divisions within the international coalition that once backed Guaido.”

The chairman of the foreign affairs committee of the US House of Representatives, Gregory Meeks, and former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson have taken the step of opening a channel of communication with the Maduro government.

Meeks’s view is that the US should recognise the new National Electoral Council (CNE) in Venezuela, which now has two opposition representatives on it. He has urged Biden to “increase engagement with the Maduro government, opposition representatives and members of civil society who played a decisive role in shaping this agreement.”

But so far the US government position, as voiced by Julie Chung, assistant secretary for western hemisphere affairs at the State Department, is that it is up to Venezuelans to decide if the new CNE board is a positive step.

The US’s treatment of Venezuela is in stark contrast to its relations, for example, with two of its client allies, Honduras and Colombia, which it continues to support despite overwhelming evidence of their governments’ corruption and brutality.

To match his progressive domestic agenda, Biden needs to seize the opportunity to break with Trump’s failed policy towards Venezuela and change his approach.

A good first step would be to accept Gregory Meeks’s suggestion and recognise Venezuela’s new National Electoral Council as a positive development. Encouraging the attendance of credible and impartial international observers at Venezuela’s next set of elections would be an additional significant step.

But more importantly, the US needs to embark on sanctions relief to enable Venezuela to rebuild its economy and crucially, to tackle the Covid-19 pandemic more effectively. This is a course of action that voices ranging from the Pope to UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres have called for.

In tandem with this, Biden would be well advised to encourage dialogue between the Maduro government and the range of opposition groups within Venezuela.

Former Spanish prime minister Jose Zapatero urged this particular approach on the US having observed Venezuela’s National Assembly elections in December 2020. In his view, “neither sanctions nor blockades are the answer. There is no better path than democracy. There will be no better tool for solving problems than dialogue and coexistence.”

Finally, Biden should cease to recognise Guaido as “interim president.” His corrupt activities, involvement in serial coup attempts, repeated calls to the military to oust Maduro and complete lack of any legal or constitutional legitimacy make him ineligible for US backing in this new, post-Trump agenda.

Join a wide spectrum of countries, organisations & prominent figures in calling for US sanctions to end illegal sanctions http://bit.ly/stopvenezuelasanctions.

This article originally appeared in The Morning Star