Briefing: The effects of the economic blockade of Venezuela

Download and view this briefing as a pdf

The blockade in context

The U.S. has been pursuing a strategy of ‘regime change’ through destabilising Venezuela dating back to the early years of Hugo Chávez’s presidency. This led George W. Bush’s administration to support the failed coup d’état against Chávez in 2002 and also the right-wing management lock-out in the oil industry. The lock-out, while ultimately unsuccessful, cost billions of dollars in lost revenues and had a catastrophic impact on the government’s social projects.

Declassified US government documents and Wikileaks material have shown that the US has subsequently used covert financial, political, media and diplomatic activities in pursuit of its goal of ‘regime change’. These have included channelling millions of US dollars to right-wing opposition groups to support their bid to destabilise and topple the elected governments of both Presidents Chávez and Maduro.

But with the repeated failure of US-financed efforts by Venezuela’s right-wing opposition to overthrow the government, even after two major campaigns of street violence and sabotage (in 2014 and 2017), the US government decided to take a central role in the strategy of ‘regime change.’

As part of this shift, the US under President Obama’s administration adopted the use of unilateral illegal sanctions against Venezuela. Under President Trump sanctions, which can take various forms, have become focused towards creating an extensive economic blockade of the type employed against Cuba since the early 1960s.

The US, with the complicity of Canada and the EU, has adopted a strategy of financial strangulation against Venezuela. This involves, amongst other aggressive measures, an oil embargo, the international blocking of bank accounts and obstruction of financial transactions outside Venezuela, severely affecting the state’s capacity to import food, medicine or anything else.

|

The intention is to attack and dislocate the country’s economic and social model, seeking its collapse in order to dismantle it. To pursue this full-scale economic war against Venezuela, the US State Dept has applied 150 coercive measures against the country. The US sanctions have been intensified since the failure of the US-backed attempted coup of Juan Guaidό, launched in January 2019. At the same time, comments from Trump himself, Vice-President Pence and Secretary of State Pompeo have included threats of military action against Venezuela. Having created the conditions (or the perception) of economic and political collapse in Venezuela |

“The pressure campaign is working. The financial sanctions we have placed on the Venezuelan Government have forced it to begin becoming in default, both on sovereign and PDVSA, its oil company’s debt. And what we are seeing… is a total economic collapse in Venezuela. So our policy is working, our strategy is working and we’re going to keep it.” Declaration by the U.S. Department of State January 9, 2018 |

through the blockade, this could take the guise of an international (i.e. US) “humanitarian intervention” in military form, or support for a coup d’état by sections of the military.

Are US sanctions legal?

US sanctions date from April 2015 following President Obama’s Executive Order a month earlier, permitting them on the grounds that Venezuela is an “unusual and extraordinary threat to US national security and foreign policy”.

Each Executive Order since then declares that because of the situation in Venezuela the United States is suffering from a “national emergency”. This designation is required by US law in order to impose such sanctions and is invoked under the 1976 National Emergencies Act.

However, there is no genuine basis for declaring Venezuela an unusual and extraordinary threat to US national security, nor in saying that the US is facing a national emergency. For President Trump, the definition of a national emergency is so flexible that he invoked the Act in February 2019 when declaring a national emergency to sidestep the need for Congressional approval for funds to build a border wall with Mexico.

The unilateral sanctions imposed by the Trump administration are illegal under the Charter of the Organization of American States (OAS), especially articles 19 and 20 of Chapter IV. They are also illegal under international human rights law, as well as treaties signed by the United States. They have no mandate from the United Nations.

The sanctions fit the definition of collective punishment of the civilian population, as described by the Geneva (Article 33) and Hague conventions, to which the USA is a signatory. In addition, given their intentional action to destroy a people, in part or in whole, and their effect on the preventable mortality of Venezuelans the sanctions also fit the UN definition of genocide.1

Alfred de Zayas, a former secretary of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) and an expert in international law, who toured Venezuela in 2018 and produced a report for the HRC, has recommended among other actions that the International Criminal Court investigate economic sanctions against Venezuela as possible crimes against humanity under Article 7 of the Rome Statute.

Idriss Jazairy, the UN’s special rapporteur on the negative impact of the unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights, has also voiced his major concerns about US sanctions against Venezuela. In January 2019 he said: “Coercion, whether military or economic, must never be used to seek a change in government in a sovereign state. The use of sanctions by outside powers to overthrow an elected government is in violation of all norms of international law.”2

What are the key sanctions that make up the blockade?

The set of US financial sanctions – to which new sanctions are continually beingadded to make them as comprehensive as possible – aims at financially asphyxiating Venezuela’s economy. The measures include:

-

the prohibition to make dividend payments or other profits to Venezuela’s government or government agency (US Executive Order 13808 of August 24, 2017)

-

all transactions related to, provision of financing for, and other dealings in, by a United States person or within the United States, any digital currency, digital coin, or digital token, that was issued by, for, or on behalf of the Government of Venezuela (US Executive Order 13827 of March 19, 2018)

-

the absolute prohibition for individuals, companies or entities to purchase Venezuelan bonds of any kind, any debt owed by the Venezuelan government, the sale, transfer, assignment, or pledging as collateral by the government or government agency (including the Central Bank and the state oil company, PDVSA) of Venezuela of any equity interest (US Executive Order 13835 of May 21, 2018)

-

sweeping new sanctions on Venezuela’s gold exports, affecting anyone trading or having anything to do with trading Venezuelan gold in the world market (Executive Order 13850 of November 2018)

-

further sanctions in January 2019 against PDVSA, which included freezing US$7 billion in assets owned by its US-based subsidiary CITGO which has three oil refineries and oversees a nationwide network of pipeline and oil and gas stations in the US

All these prohibitions apply to US persons, entities or companies and those resident or operating within US territory or any jurisdiction within the US (i.e. foreign individuals, entities or companies), but also apply everywhere else extraterritorially, where the US can exert pressure and/or enjoys support for the blockade.

How seriously has Venezuela been affected by the sanctions?

A recent report3 by the respected economists Mark Weisbrot and Jeffrey Sachs has found that “most of the impact of these sanctions has not been on the government but on the civilian population.”

Among the impacts which have disproportionately harmed the poorest and most vulnerable Venezuelans are an increase in disease and mortality (for children and adults). The report estimates that more than 40,000 deaths have since 2017-18, making the U.S. sanctions fit the definition of collective punishment as described in both the Geneva and Hague international conventions, to which the U.S. is a signatory.

How specifically have the sanctions impacted on the Venezuelan economy and people?

Venezuela as a predominantly oil-based economy is inherently vulnerable to effects of a blockade. It is the export of oil that provides the Venezuelan government with the revenue in foreign exchange that is needed to import essential goods: food, medical equipment, spare parts and equipment needed for electricity generation, water systems or transportation.

By blocking payments to Venezuela, the sanctions cut deeply into these export earnings, and therefore the government’s revenue, and reduce the government’s ability to import these essential goods.

At the same time, sanctions that constrain the Venezuelan government’s ability to operate freely in the global market further restrict its essential financial dealings.

Specifically:

-

the sanctions levied in August 2017 prohibited the Venezuelan government from borrowing in US financial markets and this prevented the government from restructuring its foreign debt through issuing new bonds

-

Executive Order (No.13808) prohibited the direct or indirect purchase of securities of all types from the Venezuelan government, thus drawing a wide range of banks and financial institutions into the net of sanctions.

Immediately, in the remaining months of 2017, a series of banks across Latin America, Europe, Asia and the United States were all unable to process standard commercial transactions with Venezuela. These included, for example:

-

a tranche of purchases of food, basic supplies and medicines worth $39 million

-

a delay of four months in the acquisition of vaccines, requiring the rescheduling of vaccination schemes in the country

|

Banks illegally retaining Venezuelan financial resources (at 30 April 2019) |

||

|

Bank |

Country |

US$ |

|

Novo Banco |

Portugal |

1,547,322,175 |

|

Bank of England |

UK |

1,323,228,162 |

|

Clearstream-London |

UK |

517,088,580 |

|

Sumitomo |

US |

507,506,853 |

|

Citibank |

US |

458,415,178 |

|

Euroclear |

Belgium |

140,519,752 |

|

Banque Eni |

Belgium |

53,084,499 |

|

Delubac |

France |

38,698,931 |

|

41 other banks and financial institutions |

17 various countries |

654,142,049 |

|

TOTAL |

5,470,030,641 |

|

As the sanctions have continued to bite, the effects have also included:

-

the withholding by Euroclear, a Belgium-based financial services company, of at least US$1.2bn that the Venezuelan

government would use to purchase food and medicines

-

US-based Citibank financial institution refused to accept money Venezuela was depositing to pay for importing a huge cargo of insulin for diabetic patients, holding up the shipment for many days in port

-

the blocking of a shipment of Primaquine, an anti-malaria medicine, from a Colombian laboratory, on the orders of its government, forcing Venezuela to buy it and other medicines for chronic illnesses in India

-

international banks suspended payments to foreign suppliers for three months, holding up the arrival of 29 container ships carrying supplies needed to process and produce food products in Venezuela

-

in September 2017, 18 million food ration packages could not be distributed because payments for food imports were blocked, requiring complex payment transactions with various allied countries to secure the imports

A clear example of how sanctions have directly impacted on vulnerable Venezuelan citizens is that 24 Venezuelan patients in Italy awaiting bone marrow transplants can no longer have their treatments and expenses paid for, as a result of the US.’s seizure of Citgo which had previously covered the costs.

Funds from Citgo worth 5 million euros ($5.57 million) allocated as payments for bone marrow transplants for Venezuelan patients and held at Portugal’s Novo Banco are frozen. As a result, to date three children have died.

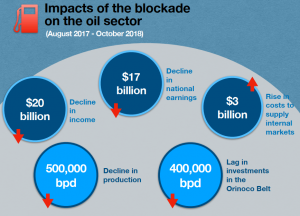

In terms of the economy, sanctions have severely impacted on the oil industry, where the loss of credit and therefore the resources to maintain production levels through maintenance and new investment led to production plummeting.

Weisbrot and Sachs have suggested that “the loss of so many billions of dollars of foreign exchange and government revenues was very likely the main shock that pushed the economy from its high inflation, when the August 2017 sanctions were implemented, into the hyperinflation that followed.”

|

Additionally, the financial sanctions carry heavy extra costs in higher interest payments, more expensive transport costs, and concrete losses from the illegally confiscated assets, whose total thus far experts calculate to be in the region of US$30 billion. How has Trump tightened the blockade in 2019? Following the Trump administration’s recognition of Juan Guaidό’s unconstitutional declaration of himself as “interim president” of Venezuela in January 2019, Executive Order 13857 extended the reach of existing sanctions to include the |

|

Central Bank of Venezuela and the state oil company PDVSA. The US’s recognition of Guaidό’s “parallel government” also brought into play sanctions implicit in previous Executive Orders.

Steps to strangle the Venezuelan economy included a ban by the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) on the use of its financial system in oil deals with Venezuela after April 2019, while also reportedly instructing oil trading houses and refiners around the world to further restrict their trade with Venezuela or face sanctions themselves, even if US sanctions did not prohibit such transactions.

The net effect of these actions has been to drastically reduce Venezuela’s ability to produce and sell oil, or to sell any foreign assets of the government since its most important foreign assets have been frozen and/or confiscated.

This has reduced still further foreign exchange earnings that would be used to buy essential imports, such that imports of goods are projected to fall by 39.4%, from $10 billion to $6.1 billion. This will undoubtedly have an even more severe impact on the lives and health of ordinary Venezuelans, especially the poorest and most vulnerable.

In particular, Venezuela has been cut off significantly from its largest oil market, the United States, which in 2018 had bought 35.6% of its oil exports. At the same time, the Trump administration has tried to pressure other countries, such as India, not to take up the slack, as well as telling oil trading houses and refiners across the world to restrict further their trading with Venezuela or face sanctions themselves, even where such dealings are not prohibited by published U.S. sanctions.

These moves were denounced as unilateral sanctions not against officials but against the general population of Venezuela by Venezuelan Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza at a United Nations meeting on April 25 2019. He went on to say: “we are campaigning for ourselves so that the world understands the consequences of the unilateral blockade of the US government on Venezuela, consequences that have taken the lives of thousands of Venezuelans.”

An immediate response by the Trump administration was to add the Foreign Minister to the list of sanctioned Venezuelan officials.

Particularly pernicious is the inclusion of Venezuela’s subsidised food programme (CLAP) in the regime of sanctions, affecting the purchase of food abroad. In late July the US followed through on an earlier threat to sanction the CLAP programme, which currently benefits six million Venezuelan families through monthly deliveries of food boxes at subsidised cost.

The US Treasury Department’s imposed sanctions against 13 companies and a number of individuals involved in the importation of food, with further discussions taking place to target sanctions on companies in Brazil, Mexico and elsewhere supplying food to Venezuela. The intention seems to be to starve the population into submission.

The US makes it a total blockade

The US blockade has been condemned by the 120-country Non-Aligned Movement at its summit in Caracas in July, the ALBA-TCP countries, a host of individual countries and in demonstrations worldwide.

The Sao Paulo Forum that ended on 28 July 2019 similarly called for “the broadest global solidarity with the defence of the sovereignty and self-determination of the Venezuelan people and with their right to live in peace”.

However, the Trump administration responded by issuing Executive Order 13884 on 5 August creating a total blockade of Venezuela. The Order freezes all Venezuelan assets in the United States and empowers the US Treasury Department to issue secondary sanctions against non-US third parties doing any type of business with the Venezuelan government, not just in the oil, banking and mining sectors.

The now former National Security Adviser John Bolton told a meeting of foreign governments in Lima the following day that “we want to send a message to third parties wanting to do business with the Maduro regime: there is no need to risk your business interests with the United States…”

The extraterritorial nature of the sanctions has been criticised by the EU, the UN and OPEC. But the additional sanctions were welcomed by the self-proclaimed ‘interim president’ Juan Guaidó.

President Maduro’s response was to cancel the government’s attendance at the dialogue negotiations mediated by Norway that were scheduled for later that week in Barbados, with Venezuelan Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza speculating that the US was “trying to dynamite the dialogue.” Nevertheless, the Bolivarian government led by President Maduro has reiterated its willingness to continue to seek dialogue – in total contrast to US efforts to use force, coercion and violence – as the only way forward.

Is Britain involved in any way with sanctions on Venezuela?

Through its involvement in the European Union, the British government is a supporter of the sanctions regime unanimously agreed by the EU in November 2017, which consisted of sanctions targeted at 18 senior individuals, coupled with demands for Venezuela to ensure what it called ‘free and fair elections’ and the release of what it deemed were ‘political prisoners’.

In a speech at Chatham House, the then Minister of State for the Americas Sir Alan Duncan warned that should the Venezuelan government not accede to the demands, fresh sanctions would be considered with Britain’s international partners.

In addition, the Bank of England, although nominally independent of the government, has taken its lead from the government by stopping 31 tonnes of Venezuelan gold deposited in its vaults, worth almost £1 billion, from being repatriated to its rightful owners, the Venezuelan government.

What is Venezuela Solidarity Campaign’s position?

VSC is clear that the blockade will not help Venezuela’s people at all but simply exacerbate the country’s problems and divisions. Sanctions will not help to facilitate a national dialogue to resolve Venezuela’s issues.

As a campaign, we will continue to work to:

-

support Venezuela’s right to national sovereignty and reject external intervention

-

demand respect for international law

-

obtain the immediate and unconditional lifting of all economic and financial sanctions, which are illegal under international law and have criminal consequences

-

support a process of dialogue to resolve differences.

1 UN Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect Genocide, https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/genocide.shtml

2 United Nations Human rights, office of the High Commissioner, http://bit.ly/2WNp6U2

3 ‘Economic Sanctions as Collective Punishment: The Case of Venezuela’ by Mark Weisbrot (Co-Director at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) and Jeffrey Sachs (Professor of Economics and Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University), CEPR, April 2019.